Monday, December 05, 2011

Tuesday, November 29, 2011

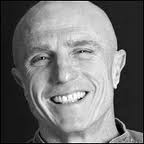

100 Days of Gratitude - Day 14: Bill Easterly

If there were a Top 1 List of Thinkers about Development Aid, Bill Easterly would probably be on it. There are now several excellent development economists publishing (and doing!) micro-level work on a variety of subjects, but none is influencing the overall debate more than Bill. His birds-eye, macro-level take on the aid industry is slowly but surely changing the way people think.

Bill joined the World Bank in 1985, and over time he realized what many of us did: namely that many of the most ambitious aid projects were failing to have much impact. And then, in the late 1990s, he did what none of the rest of us had the guts to do: he wrote about it, in a seminal book, The Elusive Quest for Growth, and in an article in the Financial Times. His courage led to his involuntary departure from the World Bank soon thereafter.

Over the past decade, Bill has tirelessly and relentlessly picked apart - on both theoretical and empirical grounds - the idea that top-down and expert-driven projects work. He coined the term Searchers vs. Planners, and drew analogies to how well functioning economies work compared centrally planned economies. His work offended not only his former employer, but also many of the new foundations that were created with money from very smart and successful entrepreneurs.

To draw attention to the debate, Bill has employed a number of rhetorical devices and flourishes that have rubbed a lot of people the wrong way. But I am struck by how often people in big aid agencies have told me that, to be honest, they agree that their own institutions - and leaders - are stymying new ideas and experimentation. "If only they would let me try X," is a frequent lament. And over the last few years, I have noticed a significant increase in the number of people in big agencies (especially the World Bank) giving access to new ideas from different sources. There is increased understanding that innovation comes from iterated, experimentation; and that failure is necessary for success.

This week, a Kenyan economist published the results of a randomized controlled trial of a Millennium Village Project (MVP) in her country. The MVPs are (hopefully) the last hurrah of the big top-down approach to development. The study found, in the words of Michael Clemens of the Center for Global Development:

Bill joined the World Bank in 1985, and over time he realized what many of us did: namely that many of the most ambitious aid projects were failing to have much impact. And then, in the late 1990s, he did what none of the rest of us had the guts to do: he wrote about it, in a seminal book, The Elusive Quest for Growth, and in an article in the Financial Times. His courage led to his involuntary departure from the World Bank soon thereafter.

Over the past decade, Bill has tirelessly and relentlessly picked apart - on both theoretical and empirical grounds - the idea that top-down and expert-driven projects work. He coined the term Searchers vs. Planners, and drew analogies to how well functioning economies work compared centrally planned economies. His work offended not only his former employer, but also many of the new foundations that were created with money from very smart and successful entrepreneurs.

To draw attention to the debate, Bill has employed a number of rhetorical devices and flourishes that have rubbed a lot of people the wrong way. But I am struck by how often people in big aid agencies have told me that, to be honest, they agree that their own institutions - and leaders - are stymying new ideas and experimentation. "If only they would let me try X," is a frequent lament. And over the last few years, I have noticed a significant increase in the number of people in big agencies (especially the World Bank) giving access to new ideas from different sources. There is increased understanding that innovation comes from iterated, experimentation; and that failure is necessary for success.

This week, a Kenyan economist published the results of a randomized controlled trial of a Millennium Village Project (MVP) in her country. The MVPs are (hopefully) the last hurrah of the big top-down approach to development. The study found, in the words of Michael Clemens of the Center for Global Development:

Because this project is large and intensive, spending on the order of 100% of local income per capita, it is reasonable to hope that it might substantially raise recipients’ incomes, at least in the short term...Wanjala and Muradian find that the project had no significant impact on recipients’ incomes.The reasons for the failure (you can read the whole post here) is one that many aid workers have learned over the past decades of traditional aid projects. The reason would have been obvious to the villagers, if their views had been genuinely solicited. But it is surely a surprise to the planners who designed the project. Too bad they did not consult Bill.

Sunday, November 27, 2011

Friday, November 25, 2011

Wednesday, November 02, 2011

100 Days of Gratitude - Day 11: Nancy Mellon

My son has severe-to-profound hearing loss. For the first three years of his life, he had little access to sound. About six months ago, we got him hearing aids, which enabled him to hear some, but not all sounds (he had especially trouble with the high pitches, including sounds like "sh" and "th", which are critical for understanding language.)

Recently - at age 4 - he received a cochlear implant at Johns Hopkins. The implant gives him excellent access to the full spectrum of sounds. But now he faces the monumental task of learning to associate those sounds with meaning - and to turn around and make the same sounds back to other people in conversation.

Most babies start the process of understanding oral language and beginning to speak from day 1 of their lives. Playing catch up is very difficult for kids who are more than a year or two old. Fortunately, Nancy Mellon, who faced a similar situation with her son 18 years ago, decided that she was not going accept what was then seen as inevitable - i.e., delayed and impaired language acquisition for her son. So she went out and did the research and found the most experienced and enlightened people in the field and decided to start a school specifically dedicated to kids like her son and mine.

Nancy and her team founded the River School in 2000, initially with only five students. It is now a thriving community of well over two hundred students, ranging from infant to third grade. Instead of segregating kids with hearing loss in separate classes, Nancy decided her school would mix them in with very verbal kids without hearing loss, while providing intensive language coaching to the kids with hearing loss. The goal is to get the kids with hearing loss mainstreamed into regular schools by third grade.

Nancy's own son just recently graduated from high school and headed off to one of the best colleges in the country. My son is just starting, but so far so good. He likes it, has great teachers, and is making steady progress. And for that, I am extremely grateful to Nancy.

Recently - at age 4 - he received a cochlear implant at Johns Hopkins. The implant gives him excellent access to the full spectrum of sounds. But now he faces the monumental task of learning to associate those sounds with meaning - and to turn around and make the same sounds back to other people in conversation.

Most babies start the process of understanding oral language and beginning to speak from day 1 of their lives. Playing catch up is very difficult for kids who are more than a year or two old. Fortunately, Nancy Mellon, who faced a similar situation with her son 18 years ago, decided that she was not going accept what was then seen as inevitable - i.e., delayed and impaired language acquisition for her son. So she went out and did the research and found the most experienced and enlightened people in the field and decided to start a school specifically dedicated to kids like her son and mine.

Nancy and her team founded the River School in 2000, initially with only five students. It is now a thriving community of well over two hundred students, ranging from infant to third grade. Instead of segregating kids with hearing loss in separate classes, Nancy decided her school would mix them in with very verbal kids without hearing loss, while providing intensive language coaching to the kids with hearing loss. The goal is to get the kids with hearing loss mainstreamed into regular schools by third grade.

Nancy's own son just recently graduated from high school and headed off to one of the best colleges in the country. My son is just starting, but so far so good. He likes it, has great teachers, and is making steady progress. And for that, I am extremely grateful to Nancy.

Wednesday, October 19, 2011

100 Days of Gratitude - Day 10: Kyle Peters

"This movie is terrible," Kyle told me as he tossed the six-part VHS boxed set onto my desk.

"What do you mean? I thought it was great," I replied.

"I watched it six times, and the South never won once."

It was 1991, and I was working at the World Bank's office in Jakarta. Kyle Peters - a Virginian - was a colleague, much senior to and wiser than me. I had lent him Ken Burns's The Civil War, which had just come out the year before.

As a young economist, I felt bewildered by the arcane jargon and knowingness of the Bank's culture. There were a lot of things that did not make sense to me, and I felt as though I were simply not smart enough to understand.

Over the couple of years that we worked together, Kyle kept me sane. Though he would never admit it, he took the mission of the Bank very seriously. But he made merciless fun of the bureaucracy and had no fear of skewering pompous people who wielded rules as if they were divine revelations or who pretended to know more than they did.

Along the way, Kyle taught me how to tell a coherent story about an economy instead of writing in the "this is up and that is down" style that our boss Russ Cheatham hated so much. He also taught me the ins and outs of the Bank's mysterious economic modeling tool, called RMSM, which required the user to make a judicious judgment about productivity to balance the books (Kyle would pretend to be deep in thought for 10 seconds before hitting a key, and when I would ask him about his thought process he would tell me it was a secret).

To the Bank's credit, Kyle is now the Director of Operational Policies, in charge of trying to align the processes with what makes sense for the Bank's mission. I guess this means that he has to make fun of himself now. In any case, I am most grateful to Kyle - a mentor, colleague, and friend - for teaching me how to keep caring about core issues even when bureaucracies sometimes conspire to make one cynical. Thanks, Kyle.

PS: Please don't tell him about this, because he will make fun of me for writing it.

"What do you mean? I thought it was great," I replied.

"I watched it six times, and the South never won once."

It was 1991, and I was working at the World Bank's office in Jakarta. Kyle Peters - a Virginian - was a colleague, much senior to and wiser than me. I had lent him Ken Burns's The Civil War, which had just come out the year before.

As a young economist, I felt bewildered by the arcane jargon and knowingness of the Bank's culture. There were a lot of things that did not make sense to me, and I felt as though I were simply not smart enough to understand.

Over the couple of years that we worked together, Kyle kept me sane. Though he would never admit it, he took the mission of the Bank very seriously. But he made merciless fun of the bureaucracy and had no fear of skewering pompous people who wielded rules as if they were divine revelations or who pretended to know more than they did.

Along the way, Kyle taught me how to tell a coherent story about an economy instead of writing in the "this is up and that is down" style that our boss Russ Cheatham hated so much. He also taught me the ins and outs of the Bank's mysterious economic modeling tool, called RMSM, which required the user to make a judicious judgment about productivity to balance the books (Kyle would pretend to be deep in thought for 10 seconds before hitting a key, and when I would ask him about his thought process he would tell me it was a secret).

To the Bank's credit, Kyle is now the Director of Operational Policies, in charge of trying to align the processes with what makes sense for the Bank's mission. I guess this means that he has to make fun of himself now. In any case, I am most grateful to Kyle - a mentor, colleague, and friend - for teaching me how to keep caring about core issues even when bureaucracies sometimes conspire to make one cynical. Thanks, Kyle.

PS: Please don't tell him about this, because he will make fun of me for writing it.

Tuesday, October 18, 2011

100 Days of Gratitude - Day 9: Keith Yamashita

|

| Keith Yamashita |

"Painful," I replied.

"Excruciating?"

"To say the least."

I went to visit Keith Yamashita, co-founder of SYPartners, in 2003, when we were struggling. We had about $50 in the bank (I had no idea how we were going to make payroll the next week), the site was struggling, and I felt incredibly lonely and isolated.

Keith and I sat in the lounge of his office talking for about 45 minutes, as he tried to get his arms around our challenges. Just having someone understand was therapeutic. But more than that, his firm helped us out periodically over the next several years. First Keith and his colleagues helped us change our name (from the wonky DevelopmentSpace, which I loved, to GlobalGiving, which I initially disliked intensely, but proved to be much better for users). And then they helped us refine our strategy and vision.

The bulk of the credit for our success goes to our awesome team. But along the way, over the last eleven years, there have been a couple of people whose encouragement and understanding kept us going at junctures when we could much more easily have given up. Keith was one of them. Thanks, Keith.

Friday, October 07, 2011

100 Days of Gratitude - Day 8: Dave Goldwyn

I met Dave in graduate school in 1983. I kind of stumbled into grad school by accident. By contrast, Dave was one of these whiz kids who was getting not only a Masters Degree, but also a JD at the same time. He went on to work at the US State Department, UN, and Department of Energy, where he was Assistant Secretary for International Affairs. Most recently he was the State Department's Special Envoy and Coordinator for International Energy Affairs, before stepping down to run his own firm. Along the way, he spared the time to help Mari and me found GlobalGiving as its first Board Chairman. His counsel, advice, and moral support during the first years of our existence were pivotal to our survival and eventual success. But most of all Dave has been a good friend, through thick and thin, over the years. And for that I am most grateful. Thank you, Dave.

Thursday, October 06, 2011

Monday, October 03, 2011

Why I May Quit Facebook (and Why They Don't - and Shouldn't - Care)

|

| The envelope of the future? |

Fortunately, I noticed right away, and changed my settings. But how often am I in a hurry and don't realize what I have done? It used to be that the most you could do was accidentally email things to a few extra people in your address book. It is now getting easier and easier to inadvertently "email" something to everyone in the world.

It would not have been a disaster if my mom's estate details (including some correspondence with my siblings) had been made public. There were no trade secrets involved. But it would have been an inadvertent breach of trust on my part vis a vis my relatives. And the things in there are really no one's business but ours.

Many things in our lives are no one's business but our own. All but the most extreme proponents of social media would say the same. We have all read about the folks who put a live web cam in their house to let the world see their every movement. But those are in the minority. The rest of us like some degree of privacy.

Don't get us wrong: we do like the way that social media enable us to share and stay in touch with various concentric circles of friends and acquaintances. We just don't want to have to worry that every time we go on line that we are inadvertently sharing with more than the people we want to. We don't want to develop a twitch when it comes to communicating, fearful that we have spoken too loud and others have overheard our private conversations.

The other night at dinner, I was extolling the virtues of Spotify to my friend C. I wanted him to listen to some music I had discovered. Instead, I got a blast from him: "I tried to sign up for Spotify, but they would only let me do so if I signed up via Facebook, so I told them to go to hell." Sure that he was wrong, I told him to stop being such a Luddite and go back and read the fine print to find where he could sign up by email. I heard nothing, so the next day I went and looked at the site myself. Low and behold, he was right. Spotify had made some deal with Facebook whereby all new users are now required to sign up via Facebook. (I got in under the old regime.)

Spotify got some blow back for its new policy, and in response made clear that new users could opt out of sharing all their music automatically via Facebook. But this was the exception (the opt-out) vs the rule (the default). And more and more this requirement to actively opt out has been adopted by Facebook and others.

And you know what? From a business point of view, what Spotify and Facebook are doing makes sense because of the power of network mathematics. Most social media sites make money from the number of items viewed. The new default of open sharing increases geometrically the number of items shared and the number of people who view them. Someone will soon (if they have not already) do some little back of the envelope calculations on this, but I would bet that the new open sharing policy increases the number of item views on each platform by a factor of 100 or more. Not all of those views are high quality views, but you get the idea. This increase in views for the system as a whole far outweighs the loss to the system if a few people drop out.

The bottom line is that, unless people leave Facebook and Spotify in droves, it makes sense for these companies to stick to their guns. Sure, there will be people like my friend C who never signs up in the first place, and possibly me, who decides to delete my account because I don't want to develop a "twitch." But the loss from us will be minor, comparatively speaking. The more I think about it, the more I want to become an investor in Facebook and Spotify, and the less I want to be a user.

Sunday, October 02, 2011

If you are feeling old...

|

| Spruce Gran Picea #0909-6B37 (9,550 years old; Fulufjället, Sweden) |

In my own travels, I have seen a few things (mostly trees) dated at roughly 2,000 years old.

But this spruce in Sweden is over 9,500 years old.

[HT: Patrick Whittle]

Friday, September 30, 2011

100 Days of Gratitude - Day 6: Jon Katz

|

| Jon Katz and Rose |

His pieces always make me smile, or even laugh. And it is rare when something he writes doesn't make me think about my own life, and what is important.

Thank you, Jon.

Monday, September 26, 2011

100 Days of Gratitude - Day 5: Yukon Huang

|

| Yukon Huang |

"Sure, I said," and I walked in my boss's door, closed it, and sat down.

It was March 1993, and I had recently returned from a five-year stint in the World Bank's Jakarta office to start work in the Bank's new Russia department. My new boss was Yukon Huang.

"I've been thinking about you," said Yukon.

"Great," I replied, and smiled. I was flattered, because Yukon was known to be a pretty tough character.

"You know, I 've been looking at your file and I see you haven't done a damned thing since you started working at the Bank seven years ago."

I was stunned. "What? What do you mean?" And I started blabbering, listing things I had worked on over the years, many of them prestigious Bank initiatives.

Yukon replied, "Sure, you have worked on various reports and projects. I know, I read about them. But you haven't really DONE anything. You are one of these guys who knows how to talk in meetings, how to dress, how to act, all that. But what have you really achieved? Nothing, as far as I can tell."

Silence. I didn't know what to say. So I just sat there for a minute or so, anxiety rising in my gut.

"So why are you telling me this?" I finally squeaked.

"Because we have a problem with [one of our projects] in Russia," Yukon replied. "And I want you to fix it."

"But I am not an expert in that area."

"I know that," he replied. "And that is why I picked you to fix it."

"What am I supposed to do?" I asked.

"Just do what makes sense," he replied.

So that's what I tried to do, with a great team, over the next couple of years. We did not solve all the problems (far from it), but we made some progress and had an impact.

That conversation, seven years after I started working, marked the beginning of my real career, and it has heavily influenced my trajectory (and life) ever since.

For that, I could not be more grateful. Thank you, Yukon. Everyone should be so lucky as to have a boss like you sometime (hopefully early) in their career.

Monday, September 19, 2011

100 Days of Gratitude - Day 4: Ann Corwin

"Why are you looking so down?" Ann asked.

"Dunno," I replied.

"Where are you going to work next year?"

"Dunno."

"Well, where have you applied?"

"I haven't really applied for any jobs yet."

"Dennis, you have to apply for jobs to get them," she said, looking down over her glasses at me. "They aren't going to just fall from the sky for you."

"Maybe. Yes, I guess you are right."

"So what about the World Bank. Why don't you apply to the World Bank?"

"Are you crazy? The Bank takes only PhDs. They haven't hired someone with only a masters degree like me in years. The application even says PhD strongly preferred."

"Well, Dennis, I've never noticed that you have particularly great respect for authority or for any of the rules around here. I would say stop your whining and apply to the World Bank. What the heck, the worse can happen is you waste a few hours."

The date was late 1985, and the scene was the placement office at Princeton's Woodrow Wilson School. I was sitting in front of the desk of Ann De Marchi (now Ann Corwin), who was then the secretary to the placement director (now she is the director).

"Now go away; I am busy," Ann told me, and she handed me an oatmeal cookie from the large glass jar she kept filled on her desk.

I did go away. And I filled out the application. And nine months later, I was sitting in an office at the World Bank, beginning the career that has brought me to where I am today.

Ann has been a good friend and colleague ever since. And for that, I am very grateful.

Why Entrepreneurship Matters

This nice "whiteboard lesson" from the Kauffman Foundation explains why entrepreneurship is critical to the US economy. I wonder how many other foundations are able to convey the importance of their mission so convincingly in three minutes?

Thursday, September 08, 2011

100 Days of Gratitude - Day 3: Debra Dunn

|

| Debra Dunn |

From that moment, Debra played a pivotal role in the evolution and success of GlobalGiving. She helped connect us to our first software engineers, introduced us to other progressive companies in Silicon Valley, and helped us meet funders. In 2002, she decided that HP employees should be able to give to causes not only in the US but around the world. She took a chance by asking us, a very new organization, to provide an online platform to do this.

Our work with HP led to similar work with many other innovative companies over the subsequent years, during which time we were extremely fortunate to have Debra join our board and help lay the foundation for what GlobalGiving has become. But most importantly, over that time, Debra - who is now teaching at the Stanford d. School - became a friend. Thank you, Debra.

Monday, September 05, 2011

100 Days of Gratitude - Day 2: Randy Komisar

|

| Randy Komisar |

That note from Randy helped give me the courage to leave a high-paying, secure, prestigious post and take a leap into the unknown. And over the past decade, Randy's steady presence in the background has been a guiding force for us through both good times and bad. His experience at Apple, General Magic, Lucas Arts Entertainment - and most recently Kleiner Perkins - gives him insights few others have. Often he pushed us to do something two years before we realized it needed to get done.

His most recent book, with John Mullins, is Getting to Plan B, which Bob Sutton describes as "more than the most useful book I've ever read on entrepreneurship." I am most grateful for Randy's friendship and support over the past decade. Thank you, Randy.

Tuesday, August 30, 2011

100 Days of Gratitude - Day 1: Lee Whittle

|

| Mom and me, 1979. |

To say my mom was an iconoclast would be an understatement. She came from a hard-scrabble immigrant family that did not know how to provide warmth to children. For some reason, my mom decided that she would be different, and she set out to create for herself and her kids a life of love and affection. Sometimes she drove us crazy with her compliments and encouragement, especially since it was never offset with any criticism. It was only later in life that I realized how rare it is to grow up with such a mother. Last week my sister found my mom's calendar, and on it was an entry for the following week that said "Wednesday: make sure to compliment [one of my siblings] on her photographs." That pretty much summed up my mom.

Let there be no mistake. Mom could be irascible and stubborn. One thing that drove me crazy earlier in life was her almost pathological inability (or unwillingness) to acknowledge the downsides of life. But one dark day a few years back, when I was struggling with a setback, my mom called me on the phone and read me the following poem by Langston Hughes. She knew the score. And I will miss her something fierce.

Mother to Son

Well, son, I’ll tell you:

Life for me ain’t been no crystal stair.

It’s had tacks in it,

And splinters,

And boards torn up,

And places with no carpet on the floor—

Bare.

But all the time

I’se been a-climbin’ on,

And reachin’ landin’s,

And turnin’ corners,

And sometimes goin’ in the dark

Where there ain’t been no light.

So boy, don’t you turn back.

Don’t you set down on the steps

’Cause you finds it’s kinder hard.

Don’t you fall now—

For I’se still goin’, honey,

I’se still climbin’,

And life for me ain’t been no crystal stair.

Langston Hughes, “Mother to Son” from Collected Poems. Copyright © 1994 by The Estate of Langston Hughes. Reprinted with the permission of Harold Ober Associates Incorporated.

Source: The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes (Vintage Books, 1994

Source: The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes (Vintage Books, 1994

Saturday, August 20, 2011

100 Days of Gratitude - Prelude

This year I turned fifty, which I expect is about the half-way point for me. I have had my share of pain and struggles and failures and disappointments. But on balance, I have had a rich and rewarding life, with great friends and a loving family. And hopefully I have given something back along the way.

As I wrote recently, some of what I have achieved has been under my own steam. I have worked reasonably hard (though not as hard as many people); I have a decent brain (though it's not the biggest around); and I am a fairly nice and thoughtful person a lot of the time (those who have seen my temper will snicker, rightfully, at this).

But I have also been lucky. And in particular I have had many wonderful family members, mentors, colleagues, and friends along the way, and I have gotten at least one big lucky break for every several bad breaks. For all of these, I am grateful, since they are in large part responsible for whom I am, and for the rich life I have lived.

So I want to devote a few posts - one hundred of them - to recognizing some people and things that have made a big difference in my life. This is an experiment that may fizzle out fast. Or it may go on beyond one hundred, who knows. (In any case, I am sure that I will miss many people and things that have made a difference, and for that let me apologize in advance.) There will be no rhyme or reason to the order in which the posts come.

As I wrote recently, some of what I have achieved has been under my own steam. I have worked reasonably hard (though not as hard as many people); I have a decent brain (though it's not the biggest around); and I am a fairly nice and thoughtful person a lot of the time (those who have seen my temper will snicker, rightfully, at this).

But I have also been lucky. And in particular I have had many wonderful family members, mentors, colleagues, and friends along the way, and I have gotten at least one big lucky break for every several bad breaks. For all of these, I am grateful, since they are in large part responsible for whom I am, and for the rich life I have lived.

So I want to devote a few posts - one hundred of them - to recognizing some people and things that have made a big difference in my life. This is an experiment that may fizzle out fast. Or it may go on beyond one hundred, who knows. (In any case, I am sure that I will miss many people and things that have made a difference, and for that let me apologize in advance.) There will be no rhyme or reason to the order in which the posts come.

Thursday, August 18, 2011

In Defense of Aid

Someone asked me the other day if I believed in aid. "You have been so critical of the aid system," he said. "Why don't you just do something else?" In response, I related the following.

In the 1970s, a combination of factors left a ten year-old boy living on and off below the poverty line, with four siblings at home and a single mother. His mother stayed at home to take care of his pre-school age sister, because child care would have cost more than any salary she could make; she did not have a college degree and had few marketable skills. The small city he lived in had few economic opportunities; it once had been prosperous, but its main industry (textiles) had moved away, and the city was down at the heels and felt grim. The boy delivered newspapers and scooped ice cream to make a little money, but it was not enough to make a fundamental difference to his circumstances.

Fortunately, there was a school lunch program that enabled the boy to get reduced price meals at noon. He had to stand in a separate line with a separate color ticket, which he found humiliating, but there was nothing he could do if he wanted lunch. As the impact of inflation reduced the real value of the family's fixed income, the school system even allowed the boy to get free lunches. Free lunches involved yet another color ticket with even greater stigma, but the boy used them when he had to, and he ate decent lunches.

In a couple of years, when the boy's youngest sister was able to go to school, the boy's mother enrolled in a government-funded job training program. It was not particularly well run, but it did give her some basic skills, and provided a structure for her to search for a job. Eventually she got a few jobs, not great ones at first, but she kept at it, and after a time she found an excellent employer with whom she eventually stayed for many years. Her paychecks helped stabilize the family's income, and helped make up for the effects that the big inflation of the '70s had taken on it.

As the boy moved up through the grades, he was determined to make something of himself and he studied hard. But he also got lucky. A private school thirty miles away offered him a full scholarship, including room and board. This was a big break for him. The school was good academically, and it made the boy much more worldly by introducing him to networks that would make it easier for him professionally in the future. He was not the top student in the class, but he did well enough so that a private foundation offered him a full scholarship for four years at an excellent state university. The foundation was so open-minded that they even gave him a grant to travel around the world one semester to study international development.

When he decided to go to graduate school, that school offered him a generous scholarship funded by a private donor. And the school helped the boy (well, he was 24 years old by then), take a year off to work in the Philippines to get some real experience, so that he would be more marketable on the job market.

At age 25, after finishing his graduate degree, the boy got a real job - a good job - where he was able to pay his own way. He spent the next 25 years in international development, (hopefully) doing some good in the world.

That boy received a lot of aid along the way. Some of it was public aid, and some of it was private aid, some in the form of loans, but most in the way of grants.

That boy was me. And that success story is why I remain optimistic about aid, despite its many failures and disappointments. I think that if we try hard, think critically, and work together, we can make aid as effective for millions of others as it was for me.

In the 1970s, a combination of factors left a ten year-old boy living on and off below the poverty line, with four siblings at home and a single mother. His mother stayed at home to take care of his pre-school age sister, because child care would have cost more than any salary she could make; she did not have a college degree and had few marketable skills. The small city he lived in had few economic opportunities; it once had been prosperous, but its main industry (textiles) had moved away, and the city was down at the heels and felt grim. The boy delivered newspapers and scooped ice cream to make a little money, but it was not enough to make a fundamental difference to his circumstances.

Fortunately, there was a school lunch program that enabled the boy to get reduced price meals at noon. He had to stand in a separate line with a separate color ticket, which he found humiliating, but there was nothing he could do if he wanted lunch. As the impact of inflation reduced the real value of the family's fixed income, the school system even allowed the boy to get free lunches. Free lunches involved yet another color ticket with even greater stigma, but the boy used them when he had to, and he ate decent lunches.

In a couple of years, when the boy's youngest sister was able to go to school, the boy's mother enrolled in a government-funded job training program. It was not particularly well run, but it did give her some basic skills, and provided a structure for her to search for a job. Eventually she got a few jobs, not great ones at first, but she kept at it, and after a time she found an excellent employer with whom she eventually stayed for many years. Her paychecks helped stabilize the family's income, and helped make up for the effects that the big inflation of the '70s had taken on it.

As the boy moved up through the grades, he was determined to make something of himself and he studied hard. But he also got lucky. A private school thirty miles away offered him a full scholarship, including room and board. This was a big break for him. The school was good academically, and it made the boy much more worldly by introducing him to networks that would make it easier for him professionally in the future. He was not the top student in the class, but he did well enough so that a private foundation offered him a full scholarship for four years at an excellent state university. The foundation was so open-minded that they even gave him a grant to travel around the world one semester to study international development.

When he decided to go to graduate school, that school offered him a generous scholarship funded by a private donor. And the school helped the boy (well, he was 24 years old by then), take a year off to work in the Philippines to get some real experience, so that he would be more marketable on the job market.

At age 25, after finishing his graduate degree, the boy got a real job - a good job - where he was able to pay his own way. He spent the next 25 years in international development, (hopefully) doing some good in the world.

That boy received a lot of aid along the way. Some of it was public aid, and some of it was private aid, some in the form of loans, but most in the way of grants.

That boy was me. And that success story is why I remain optimistic about aid, despite its many failures and disappointments. I think that if we try hard, think critically, and work together, we can make aid as effective for millions of others as it was for me.

Tuesday, July 26, 2011

More Art than Science

Today, during my annual physical, my doctor, who is well known and widely quoted in the Washington region, asked me what I did for a living.

I said "Oh, I work in international development." And then, after a pause, I said, "We are trying to become more scientific, by doing more randomized controlled trials like you do in the medical field."

He looked up at me sharply and laughed. "Are you crazy?" he replied. "Only a very small proportion of what I do is based on randomized trials. In fact, most medical treatments are not based on rigorous evidence at all.Whatever anyone might tell you, people are just too complex and too different to do lots of good randomized trials."

"Well, then, why do people say you are such a good doctor?" I asked him.

"I guess I may be better than other doctors at trial and error. I just get people to try things, and if they don't work, then I get them to try other things. Being a doctor is really much more of an art than a science."

I said "Oh, I work in international development." And then, after a pause, I said, "We are trying to become more scientific, by doing more randomized controlled trials like you do in the medical field."

He looked up at me sharply and laughed. "Are you crazy?" he replied. "Only a very small proportion of what I do is based on randomized trials. In fact, most medical treatments are not based on rigorous evidence at all.Whatever anyone might tell you, people are just too complex and too different to do lots of good randomized trials."

"Well, then, why do people say you are such a good doctor?" I asked him.

"I guess I may be better than other doctors at trial and error. I just get people to try things, and if they don't work, then I get them to try other things. Being a doctor is really much more of an art than a science."

Monday, July 25, 2011

World Bank as Convener 1st, Lender 2nd?

"Are you sure we should do this in the World Bank atrium?"

"Yes, sir," I said. "Why not?"

I tried to act confident, but I was terrified. It was February 1998, and on the phone was a managing director, second only in power to the president of the World Bank. He was known for asking questions that were actually orders. Arguing rather than obeying was considered ill-advised.

"Well," he said, "we may have outside visitors that day. Do you think they should see some of those crazy ideas that staff may come up with? What if we relocated the event to the basement, out of the way?"

A small innovation team, with encouragement from Jim Wolfensohn, the Bank's president, had decided to launch the first-ever Innovation Marketplace, a one-day event when any Bank staff member (regardless of title or seniority) could propose an idea for helping the Bank better fight poverty. We would award $5 million to help fund the start-up of the most promising ideas. We had decided to hold the event in the atrium of the Bank, a beautiful space that soars thirteen stories.

The only problem was that the atrium was almost never used for public events; it was always eerily quiet and deserted, even sterile. You never wanted to linger there - you always hurried through. The culture of the Bank at that time was such that everyone worked behind closed doors, beavering away on in-depth country or sector studies designed to find out the right answers to various development challenges. Staff emerged only for the occasional review meetings, or to go on mission to the countries they worked on.

My, oh, my how the world - and the World Bank - have changed since then. A couple of months ago, I went back to my old stomping grounds to witness an Apps for Development competition. Not only was the Bank's atrium a beehive of activity, but there was even techno music pumping up the mood of the crowd before the announcement of the event's winners.

Stephanie Strom recently wrote a nice article in the NY Times about how the Bank is opening its "treasure chest of data" for researchers and others around the world to use. The articles has good insights into the benefits of making data public; and the fact that the World Bank (previously among the most secretive of aid institutions) is now making such huge strides is sure to encourage other agencies to do the same. (The UNDP also created a very impressive open data portal for some of its projects.)

Sharing data is a big leap, but there is now a window of opportunity for the Bank to do something much, much bigger. Back in 1998, with my heart pounding, I stood my ground with the Managing Director, and the Innovation Marketplace was a huge success; by cutting through the usual layers of bureaucracy and giving everyone an equal voice, the event allowed all sorts of good ideas to bubble up, any many of them soon became major strategic. In some sense, we were democratizing the World Bank, even if for only one day.

Building on that success, in early 2000 we went on to launch the Development Marketplace, which allowed anyone in the world (not just the Bank) to propose an idea for funding. The planning of this event also generated a lot of controversy (and not only from senior managers this time), but it was a big success, too. And though I left the World Bank shortly afterwards to co-found GlobalGiving, the Bank went on to replicate the Development Marketplace many times, including in some seventy countries around the world over the past decade. Country directors would sometime report that it was the first time they had been able to get civil society groups and government officials in one room together talking about ideas and solutions rather than just arguing.

Nonetheless, despite their success, these marketplaces have remained peripheral to World Bank's main business. In the decade since my departure, many former colleagues complained to me that the Bank was failing to innovate in ways that would keep it relevant for a changing world.

That may be about to change. Bob Zoellick, the Bank's current president, recently talked in a speech about the "democratization" of development, where the Bank and other aid agencies no longer pretend to have a monopoly on understanding problems and devising solutions. Bank experts would still have a great deal of technical expertise, but the role of Bank staff would shift. Instead of trying to find and hire the elusive "best expert in the world on subject X," the Bank would hire very good experts who are capable of leading a conversation among other experts, government officials, and regular citizens about the most pressing problems and the most viable potential solutions. Bank staff would in a sense become "hosts" of conversations about what to do, and then would have the ability to financially support the initiatives and approaches that arise from these conversations.

Hosting effective conversations is hard, and it may be the most in-demand skill at the Bank in the decade ahead. If the Bank can make progress in this area, however, the payoff for the institution could be large. In addition, by modeling openness and an ability to listen, the Bank would be putting indirect pressure on governments around the world to do the same. If regular people are able to comment on and even contribute to the design of World Bank projects, they are surely going to begin demanding the same treatment from their own governments. The resulting increase in citizen voice and government responsiveness could end up having a far more important impact than any particular Bank project(s).

Zoellick has assembled a solid team to help the Bank remake itself. Sanjay Pradhan, Randi Ryterman, Aleem Walji, and others are helping lead a conversation within the Bank on ways to cultivate new thinking and approaches. As the NY Times article notes, significant culture change is going to be required, and that is always tough. And change will also demand hard thinking about the World Bank's business model, which currently relies on generating a spread on its loans and other financial instruments. Incentives within the institution remain tied to the ability of staff to make loans and help the institution generate the income that it needs to operate.

The good news is that the best staff at the World Bank are leading the way. A while back, some of my former colleagues hosted an informal all-day Saturday session for health officials in a Latin American country. No ties were allowed, and there was no rigid agenda. When I told one of the Bank conveners that I was sorry he had to work on a Saturday, he told me that it was one of the most productive days of his career. "For once, we did not give them a long lecture," he told me. "We just served them pizza and kept the conversation headed in the right direction, injecting bits of information but not pressing my own views too hard."

As a result, the health officials swapped stories about what was working and what wasn't in their country. They were able to be candid about their failures as well as their successes. The conversation was not about What is the RIGHT ANSWER? Rather, it was about What are some reasonable things to try in our country, and how can we best evaluate the results? The participants liked the experience so much that one of the officials present hosted a similar session, with Bank help, for other countries in the region. The effort led to a great deal of social capital that allowed successes and failures to be honestly shared, thereby speeding experimentation and improving feedback loops.

My friend told me he felt he had helped advance reform more on that single day than in months of formal meetings and expert presentations. Instead of being a Bank expert pushing for the RIGHT policy, he was helping a country's own experts iterate toward an approach that would work in their context. Furthermore, the trust and social capital that emanated from these meetings led the countries involved to seek several hundred million dollars of funding from the Bank to support their reform agendas. The revenue from these loans in turn enable the Bank staff to provide additional intellectual support, including hosting more conversations.

"Yes, sir," I said. "Why not?"

I tried to act confident, but I was terrified. It was February 1998, and on the phone was a managing director, second only in power to the president of the World Bank. He was known for asking questions that were actually orders. Arguing rather than obeying was considered ill-advised.

"Well," he said, "we may have outside visitors that day. Do you think they should see some of those crazy ideas that staff may come up with? What if we relocated the event to the basement, out of the way?"

A small innovation team, with encouragement from Jim Wolfensohn, the Bank's president, had decided to launch the first-ever Innovation Marketplace, a one-day event when any Bank staff member (regardless of title or seniority) could propose an idea for helping the Bank better fight poverty. We would award $5 million to help fund the start-up of the most promising ideas. We had decided to hold the event in the atrium of the Bank, a beautiful space that soars thirteen stories.

The only problem was that the atrium was almost never used for public events; it was always eerily quiet and deserted, even sterile. You never wanted to linger there - you always hurried through. The culture of the Bank at that time was such that everyone worked behind closed doors, beavering away on in-depth country or sector studies designed to find out the right answers to various development challenges. Staff emerged only for the occasional review meetings, or to go on mission to the countries they worked on.

My, oh, my how the world - and the World Bank - have changed since then. A couple of months ago, I went back to my old stomping grounds to witness an Apps for Development competition. Not only was the Bank's atrium a beehive of activity, but there was even techno music pumping up the mood of the crowd before the announcement of the event's winners.

Stephanie Strom recently wrote a nice article in the NY Times about how the Bank is opening its "treasure chest of data" for researchers and others around the world to use. The articles has good insights into the benefits of making data public; and the fact that the World Bank (previously among the most secretive of aid institutions) is now making such huge strides is sure to encourage other agencies to do the same. (The UNDP also created a very impressive open data portal for some of its projects.)

Sharing data is a big leap, but there is now a window of opportunity for the Bank to do something much, much bigger. Back in 1998, with my heart pounding, I stood my ground with the Managing Director, and the Innovation Marketplace was a huge success; by cutting through the usual layers of bureaucracy and giving everyone an equal voice, the event allowed all sorts of good ideas to bubble up, any many of them soon became major strategic. In some sense, we were democratizing the World Bank, even if for only one day.

Building on that success, in early 2000 we went on to launch the Development Marketplace, which allowed anyone in the world (not just the Bank) to propose an idea for funding. The planning of this event also generated a lot of controversy (and not only from senior managers this time), but it was a big success, too. And though I left the World Bank shortly afterwards to co-found GlobalGiving, the Bank went on to replicate the Development Marketplace many times, including in some seventy countries around the world over the past decade. Country directors would sometime report that it was the first time they had been able to get civil society groups and government officials in one room together talking about ideas and solutions rather than just arguing.

Nonetheless, despite their success, these marketplaces have remained peripheral to World Bank's main business. In the decade since my departure, many former colleagues complained to me that the Bank was failing to innovate in ways that would keep it relevant for a changing world.

That may be about to change. Bob Zoellick, the Bank's current president, recently talked in a speech about the "democratization" of development, where the Bank and other aid agencies no longer pretend to have a monopoly on understanding problems and devising solutions. Bank experts would still have a great deal of technical expertise, but the role of Bank staff would shift. Instead of trying to find and hire the elusive "best expert in the world on subject X," the Bank would hire very good experts who are capable of leading a conversation among other experts, government officials, and regular citizens about the most pressing problems and the most viable potential solutions. Bank staff would in a sense become "hosts" of conversations about what to do, and then would have the ability to financially support the initiatives and approaches that arise from these conversations.

Hosting effective conversations is hard, and it may be the most in-demand skill at the Bank in the decade ahead. If the Bank can make progress in this area, however, the payoff for the institution could be large. In addition, by modeling openness and an ability to listen, the Bank would be putting indirect pressure on governments around the world to do the same. If regular people are able to comment on and even contribute to the design of World Bank projects, they are surely going to begin demanding the same treatment from their own governments. The resulting increase in citizen voice and government responsiveness could end up having a far more important impact than any particular Bank project(s).

Zoellick has assembled a solid team to help the Bank remake itself. Sanjay Pradhan, Randi Ryterman, Aleem Walji, and others are helping lead a conversation within the Bank on ways to cultivate new thinking and approaches. As the NY Times article notes, significant culture change is going to be required, and that is always tough. And change will also demand hard thinking about the World Bank's business model, which currently relies on generating a spread on its loans and other financial instruments. Incentives within the institution remain tied to the ability of staff to make loans and help the institution generate the income that it needs to operate.

The good news is that the best staff at the World Bank are leading the way. A while back, some of my former colleagues hosted an informal all-day Saturday session for health officials in a Latin American country. No ties were allowed, and there was no rigid agenda. When I told one of the Bank conveners that I was sorry he had to work on a Saturday, he told me that it was one of the most productive days of his career. "For once, we did not give them a long lecture," he told me. "We just served them pizza and kept the conversation headed in the right direction, injecting bits of information but not pressing my own views too hard."

As a result, the health officials swapped stories about what was working and what wasn't in their country. They were able to be candid about their failures as well as their successes. The conversation was not about What is the RIGHT ANSWER? Rather, it was about What are some reasonable things to try in our country, and how can we best evaluate the results? The participants liked the experience so much that one of the officials present hosted a similar session, with Bank help, for other countries in the region. The effort led to a great deal of social capital that allowed successes and failures to be honestly shared, thereby speeding experimentation and improving feedback loops.

My friend told me he felt he had helped advance reform more on that single day than in months of formal meetings and expert presentations. Instead of being a Bank expert pushing for the RIGHT policy, he was helping a country's own experts iterate toward an approach that would work in their context. Furthermore, the trust and social capital that emanated from these meetings led the countries involved to seek several hundred million dollars of funding from the Bank to support their reform agendas. The revenue from these loans in turn enable the Bank staff to provide additional intellectual support, including hosting more conversations.

Thursday, July 21, 2011

Got to Admit it's Getting Better

Over the last one hundred years, the physical well being of the world's population has improved far more than in all of the previous natural history of humankind.Charles Kenny's recent book Getting Better is an antidote to the pessimism many of us feel about the state of the world. Those of us in international development f are frustrated we have not been able to find a toolkit of approaches that reliably increases growth in poor countries. Kenny acknowledges this frustration, but shows that many indicators of wellbeing have improved rapidly even in the absence of consistent economic growth:

Global average life expectancy increased from around thirty-one years in 1900 to sixty-six by 2000.In terms of GDP, there is an increasing divergence among countries in the world, with many of the poorer falling further and further behind. But with respect to other indicators of wellbeing, there is a striking convergence. Infant mortality has plunged by over half in eighty percent of the world's poor countries in the last fifty years. Literacy rates in sub-Saharan Africa rose from 28 to 61 percent from 1970 to 2000. Some very poor countries such as Vietnam have achieved 95% literacy. Democratic ideas and practices are spreading rapidly (notwithstanding big setbacks and uneven progress), and violence is way down: global homicide levels, for example, are about one-third of what they were in England in the Middle Ages.

How can this be? It turns out that it is not very expensive to improve these aspects of wellbeing. This is because of tremendous innovation in technologies and ideas in some domains, ranging from vaccines to understanding germs to oral rehydration therapy to increased agricultural productivity. In the old days, even the wealthiest and most powerful of kings died early for lack of the cheap modern vaccines that keep the most vulnerable and poor people alive today.

The state of Kerala in India, with a per capita income of $300 per year, has been able to achieve a life expectancy of 72 and a literacy rate of 91%. By comparison, the US has a per capita income of $29,000 and has a life expectancy only five years greater than Kerala. Lest we think that achieving those extra five years of life expectancy requires huge resources, take the case of Costa Rica. Life expectancy in Costa Rica is two years greater than the US, but income per capita is only $6,500, and Costa Rica spends only $305 per capita per year on health, compared to $5,711 in the US.

Getting Better is full of facts and figures such as these. Kenny neither minimizes the remaining problems (poor people do have fewer opportunities and poverty does equal misery for millions of people), but he does want to zoom out and take the long view so we can see we are making progress. He does note that the spread of even the cheap and effectives innovations he discusses has been uneven - and thus there is great scope for further progress.

Progress must often come on the demand side rather than the supply side, Kenny argues. In many (not all) cases, there is enough money in the budget for education and health programs, but people don't demand the right services for lack of knowledge about their potential effects. How to do better marketing is thus a key challenge for the aid business - an area in which we have made only modest investments. Relatively small investments in transparency measures can also help stimulate demand as well. Local people are often told that there are not enough resources in the budget to do X, Y, or Z, but once local people are able to see what the money is actually being spent on, they are able to bring to bear pressures to get what they need.

Kenny closes the book with suggestions for how to catalyze the flow of ideas and hasten the uptake of innovations in health, education, and other areas. This is the weakest part of the book, but at least he is offering a framework for further analysis and experimentation. The bad news is, as Kenny says, we don't know how to make people financially richer. The good news is that we do know how to make them better off, and that fact should motivate us all.

Monday, July 18, 2011

Bad News for Foxes?

My friend April Harding sent me this talk at the Long Now Foundation by Philip Tetlock, who has spent many years studying how well experts perform at predicting future events. Tetlock's research shows that foxes are better than hedgehogs at predicting the future.* And interestingly, the less confident people are about their predictions, the more likely their predictions are to be accurate! (Foxes also tend to be less confident than hedgehogs.)

This result makes many of us (myself included) happy, because we consider ourselves foxes. The only problem, according to Tetlock, is that even foxes barely edge out simple mathematical algorithms** when it comes to accuracy.

----------------

* Isaiah Berlin famously defined hedgehogs as people who have one big idea through which they interpret everything they see. Ideologues of all stripes are examples of hedgehogs. Foxes, by contrast, bring an eclectic set of perspectives to bear on their interpretation of events and phenomena.

**For example, things will continue unchanged. Or, things will continue to change at the same rate as in the recent past.

Wednesday, June 15, 2011

Your Worst Fear Realized

My friend Keith Hansen sent me a link to Conan O'Brien's recent graduation speech at Dartmouth. The speech is a refreshing change from the "Follow your dreams" and "Whatever you can conceive, you can do" pablum that we hear and read in so many places.

Here is an excerpt:

Here is an excerpt:

Nietzsche famously said "Whatever doesn't kill you makes you stronger." But what he failed to stress is that it almost kills you. Disappointment stings and, for driven, successful people like yourselves it is disorienting. What Nietzsche should have said is "Whatever doesn't kill you, makes you watch a lot of Cartoon Network and drink mid-price Chardonnay at 11 in the morning."Now, by definition, Commencement speakers at an Ivy League college are considered successful. But a little over a year ago, I experienced a profound and very public disappointment. I did not get what I wanted, and I left a system that had nurtured and helped define me for the better part of 17 years. I went from being in the center of the grid to not only off the grid, but underneath the coffee table that the grid sits on, lost in the shag carpeting that is underneath the coffee table supporting the grid. It was the making of a career disaster, and a terrible analogy.But then something spectacular happened. Fogbound, with no compass, and adrift, I started trying things. I grew a strange, cinnamon beard. I dove into the world of social media. I started tweeting my comedy. I threw together a national tour. I played the guitar. I did stand-up, wore a skin-tight blue leather suit, recorded an album, made a documentary, and frightened my friends and family. Ultimately, I abandoned all preconceived perceptions of my career path and stature and took a job on basic cable with a network most famous for showing reruns, along with sitcoms created by a tall, black man who dresses like an old, black woman. I did a lot of silly, unconventional, spontaneous and seemingly irrational things and guess what: with the exception of the blue leather suit, it was the most satisfying and fascinating year of my professional life. To this day I still don't understand exactly what happened, but I have never had more fun, been more challenged—and this is important—had more conviction about what I was doing.How could this be true? Well, it's simple: There are few things more liberating in this life than having your worst fear realized. I went to college with many people who prided themselves on knowing exactly who they were and exactly where they were going. At Harvard, five different guys in my class told me that they would one day be President of the United States. Four of them were later killed in motel shoot-outs. The other one briefly hosted Blues Clues, before dying senselessly in yet another motel shoot-out. Your path at 22 will not necessarily be your path at 32 or 42. One's dream is constantly evolving, rising and falling, changing course. This happens in every job, but because I have worked in comedy for twenty-five years, I can probably speak best about my own profession.Way back in the 1940s there was a very, very funny man named Jack Benny. He was a giant star, easily one of the greatest comedians of his generation. And a much younger man named Johnny Carson wanted very much to be Jack Benny. In some ways he was, but in many ways he wasn't. He emulated Jack Benny, but his own quirks and mannerisms, along with a changing medium, pulled him in a different direction. And yet his failure to completely become his hero made him the funniest person of his generation. David Letterman wanted to be Johnny Carson, and was not, and as a result my generation of comedians wanted to be David Letterman. And none of us are. My peers and I have all missed that mark in a thousand different ways. But the point is this : It is our failure to become our perceived ideal that ultimately defines us and makes us unique. It's not easy, but if you accept your misfortune and handle it right, your perceived failure can become a catalyst for profound re-invention.So, at the age of 47, after 25 years of obsessively pursuing my dream, that dream changed. For decades, in show business, the ultimate goal of every comedian was to host The Tonight Show. It was the Holy Grail, and like many people I thought that achieving that goal would define me as successful. But that is not true. No specific job or career goal defines me, and it should not define you. In 2000—in 2000—I told graduates to not be afraid to fail, and I still believe that. But today I tell you that whether you fear it or not, disappointment will come. The beauty is that through disappointment you can gain clarity, and with clarity comes conviction and true originality.

Wednesday, June 01, 2011

If Not Randomized Trials, Then What?

The above chart shows the returns to various approaches to keeping kids in school, according to research conducted by the Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL) at MIT. The results are striking. Spending $100 on public awareness in Madagascar yields a whopping 40 extra years of student attendance. $100 spent on deworming in Kenya generates an additional 28+ years of student attendance. Public awareness and deworming campaigns are 10 to 40 times more cost effective than providing school meals, scholarships, or uniforms.

J-PAL has popularized the use of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in development aid, a movement that has recently been highlighted by Nick Kristof in the NY Times. Kristof describes RCTs as the "hottest thing in the fight against poverty." And when you see striking results like those in the chart above, it is hard not to get excited.

Michael Kremer, a professor at Harvard, pioneered some of the earliest randomized trials, including those on de-worming in Kenya. He has gone on to help design and oversee USAID's new Development Innovation Ventures, which promises to seed a lot of new approaches on the condition that they be rigorously evaluated. Michael's common sense approach to finding out what works (who would have thought that de-worming would be such a high-return investment in education!) makes this USAID initiative potentially promising.

The good news about RCTs is that they can guide the design of development projects in some circumstances. For example, in the regions of Kenya where Michael did his work, the most rational allocation of education expenditures might be first to de-worm all the children. Only after that is done would it make sense to spend money on things like subsidizing uniforms. I also have argued that the expensive Millennium Village Project should be subject to an RCT "competition" with other approaches.

But promising new tools often get promoted as silver bullets, and RCTs are no exception. This inevitably causes a backlash, which in turn means that, after 15 minutes of fame, many good tools fail to be adopted to an optimal degree. Rachel Glennerster, the director of J-PAL, told Owen Barder last year that there was a risk of too much hype, and that RCTs were not feasible or desirable in all circumstances. For those interested in this topic, I recommend the full interview.

What are the limitations or even downsides of RCTs? Angus Deaton is one of the strongest critics of RCTs, for a number of conceptual and methodological reasons. He argues that any statistically valid RCT must be very narrow in terms of applicability. For example, the findings on de-worming in Kenya cannot be generalized even beyond the villages in which the experiments were run. To his point, J-PAL's chart above shows that the returns to de-worming in India are only about 10-12% of the returns to de-worming in Kenya. To the extent RCTs are so context specific, their usefulness is severely limited.

Deaton also argues that RCTs may capture the mean but not the variance of the effects that a project has on beneficiaries in the studied population. Though an initiative may on average have positive effects, it may have a negative impact on a substantial proportion (or even majority) of the beneficiary population. And vice versa: an initiative which shows a negative average impact might benefit many beneficiaries. Drawing any sweeping conclusions under these conditions, Deaton argues, is not warranted, and could even be dangerous.

Others, such as Arvind Subramanian at the Center for Global Development, argue that even if RCTs can shed light on the effect of a development project in limited circumstances, they cannot tell us anything about whether aid itself works or not.

A young researcher from within the RCT movement noted to me recently that randomized trials can only predict marginal impacts and cannot be extrapolated. For example, the effect of public information may have the effect of keeping individual kids in school one month more; providing 12 times more information will not keep the kids in school an extra 12 months, which may be the goal.

At some point, a clever economist will try to carry out a randomized controlled trial of RCTs. She will attempt to answer the question: Does the use of RCTs lead to changes in the design of aid projects that translate into improved well being for people in developing countries?

My guess is that such a meta-RCT would not show a strong positive impact, for several reasons. First is the cost of RCTs. Even if they are a gold standard (which Deaton disputes), the costs are such that they will only be able to be done on a minuscule proportion of development initiatives.

Second, the current incentive structure in the aid industry results in an attenuated link between evidence on impact and changes in project design. Aid providers face little competitive or other pressure to seek out the initiatives that have the greatest impact. In fact, Lant Pritchett argues that, under the current structure, it "pays to be ignorant" because confessing failure hurts you more than success benefits you (in terms of political and financial support).

The bottom line is that RCTs will become like Consumer Reports trials in the consumer marketplace. Consumer Reports is a useful adjunct to decision making for some things (although often I can't find the exact models they tested!) But innovation in service of improved quality and lower cost comes from market pressures arising from consumer feedback through purchasing decisions.

In the same way, the best hope for improving the impact of aid initiatives is to create much richer and more real-time feedback loops between beneficiaries and aid providers.

Instead of determining needs ex-ante through expert studies, we need to start with asking beneficiaries "What do YOU want?" New technologies and approaches enable us to do this on a far wider scale, at dramatically lower cost, than ever before. And then once a project is underway, we need to ask beneficiaries "How do YOU think it's going and what changes need to be made?" And once that project is finished, we need to ask "Given what we learned from the previous project, what is the next thing you want?" The faster we can iterate through these questions, the faster we will get to greater impact.

Naturally, experts should provide technical analysis such as RCT results to beneficiaries to help inform their responses. But in the end, we need to make the beneficiary king.

Monday, May 23, 2011

R.I.P. Aid Watch

On May 19, Bill Easterly and Laura Freschi announced that their blog Aid Watch was ending, after running about two years. I was shocked, and (after checking my calendar to make sure it was not April 1), dismayed.

Who else, I thought to myself,was going to call B.S. on the foibles and failings (and sometimes nearly criminal negligence) of certain aid agencies? Who else was going to relentlessly debunk the egomaniacal schemes of certain self-styled aid messiahs? Who else was going to have the guts to speak truth to power? Who else was going to remind us that so many new programs had been tried in the past, with disappointing if not disastrous results?

Who else, I asked myself, was going to demand each day that aid simply "benefit the poor?" Who else was going to point us toward new ways of providing aid that actually take into account what the poor want? Who else was going to contrast the failures of closed, top-down aid systems with the successes of open-access systems that provide fast, rich feedback systems? Who else was going to redefine the debate about aid?

Aid Watch was controversial from the start. Bill and Laura did not hesitate to take on sensitive issues, and they did not cloak their criticisms in vague bureaucratic language. Typical evaluations of aid programs are dense and oblique, with shortcomings buried under mounds of data and jargon. After a couple hundred pages of analysis touting the benefits of a program, official evaluations often tip their hat to failure with a paragraph beginning "But challenges remain..." And then phase two of the same program begins with only a modest modification to a fundamentally failed design.

Aid Watch specialized in cutting through all of the obfuscation to say bluntly "This does not work. We should stop it now and do something else if we really care about helping the poor."

In their valedictory post, Bill and Laura promise that the work of Aid Watch will continue, with longer and more in-depth pieces under the guise of Aid Watch's parent - the Development Research Institute (DRI), at New York University, where Bill is Professor of Economics. I, for one, am very much looking forward to the next chapter of Aid Watch.

Who else, I thought to myself,was going to call B.S. on the foibles and failings (and sometimes nearly criminal negligence) of certain aid agencies? Who else was going to relentlessly debunk the egomaniacal schemes of certain self-styled aid messiahs? Who else was going to have the guts to speak truth to power? Who else was going to remind us that so many new programs had been tried in the past, with disappointing if not disastrous results?

Who else, I asked myself, was going to demand each day that aid simply "benefit the poor?" Who else was going to point us toward new ways of providing aid that actually take into account what the poor want? Who else was going to contrast the failures of closed, top-down aid systems with the successes of open-access systems that provide fast, rich feedback systems? Who else was going to redefine the debate about aid?

Aid Watch was controversial from the start. Bill and Laura did not hesitate to take on sensitive issues, and they did not cloak their criticisms in vague bureaucratic language. Typical evaluations of aid programs are dense and oblique, with shortcomings buried under mounds of data and jargon. After a couple hundred pages of analysis touting the benefits of a program, official evaluations often tip their hat to failure with a paragraph beginning "But challenges remain..." And then phase two of the same program begins with only a modest modification to a fundamentally failed design.

Aid Watch specialized in cutting through all of the obfuscation to say bluntly "This does not work. We should stop it now and do something else if we really care about helping the poor."

In their valedictory post, Bill and Laura promise that the work of Aid Watch will continue, with longer and more in-depth pieces under the guise of Aid Watch's parent - the Development Research Institute (DRI), at New York University, where Bill is Professor of Economics. I, for one, am very much looking forward to the next chapter of Aid Watch.

Treating Employees as People

- Over the period 1998-2008, the stock of the companies voted "best to work for" appreciated nearly seven times as much as the stock of the average company.

- The most admired companies on Fortune Magazine's list had double the market returns of their competitors over a seven year period.

- Only 13 percent of unhappy employees recommend their company's products, vs 78 percent of happy employees.

Those are just some of the findings reported in Dave Ulrich and Wendy Ulrich's book The Why of Work. The authors argue that companies that treat people as just another factor of production are increasingly at a competitive disadvantage. Conversely, companies that engage their employees in a meaningful way have higher market returns.

Why? The authors offer the following possible explanations:

- "Employees are committed, productive, and likely to stay with the company

- Customers pick up on employee attitudes and are more likely to do business with the company

- Investors have confidence in the company's future, giving it a higher market value

- The company's reputation in the community is enhanced."

There are many approaches to creating a meaningful work environment. One of the simplest (if still rare) is just to treat employees like real people, with valuable insights and instincts for what is best for the business. Another is for the company to engage with the broader communities where it does business, by providing mentoring and volunteering and/or by financially supporting schools, clinics, and other social initiatives. In other words, by treating the broader community members as real people.

What if all businesses treated their employees and customers this way?

Monday, May 16, 2011

Innovation and Parallel Processing

Tim Harford